Romanian Revolution of 1989

Miscellanea / / November 13, 2021

By Guillem Alsina González, in May. 2018

For those of us who are already a certain age and have fully seen conscience about what was happening, the fall of the Berlin Wall, without a doubt one of the iconic images of everything that It happened throughout those months, and that was a process that not only affected Germany, it was the summary execution of Nicolae Ceausescu.

For those of us who are already a certain age and have fully seen conscience about what was happening, the fall of the Berlin Wall, without a doubt one of the iconic images of everything that It happened throughout those months, and that was a process that not only affected Germany, it was the summary execution of Nicolae Ceausescu.

The Romanian revolution of 1989 was the revolutionary process by which the people abolished the regime Communist established after World War II and personified by the dictator Nicolae Ceausescu.

The seizure of power had its chiaroscuro, as we will see below, so, as in all revolutionOne wonders to what extent the people really took power.

The general boredom of the population Romanian anti-regime came mainly from two vectors: on the one hand, the economic crisis that gripped all the countries of communist eastern Europe and, on the other, the lack of freedoms civilians.

Ceausescu had been hardening his politics interior over time, hardening the repression within as his

family she lived in increasingly obscene luxury. If the majority of Romanians lived in poverty, he and his people were wasting hands full.Another addition that unnerved the citizenship Romanian was the imposition of draconian economic measures, aimed at liquidating the foreign debt of the country in a few years, but which impeded growth and undermined the standard of living of the citizens of a foot.

The "Conductor"As he called himself (in Romanian it means" driver "), he had come to destroy practically the entire historical Bucharest to turn the city into a monster to suit him, according to his wishes.

The cult aura of personality that Ceausescu promoted made her disconnect from reality, creating a new one, which prevented her from seeing where events would go and, therefore, prevent her own fall.

As a result of general boredom, and with news that reached the officers through "alternative" channels, the revolt that was to end the regime began in Timisoara on December 16, 1989.

The city, located in the west of the country near the borders with Hungary and the former Yugoslavia, saw in the eviction of a Lutheran pastor, a escalation of events that led from the original protest - which lost its importance - to an anti-government and anti-regime protest communist.

The events escalated rapidly, and what was a peaceful protest led to a street fight by activists against the local police forces and the Securitate, the Romanian political secret police.

The next day, as the unrest continued, the regime decided that the army would take care of the problem. Big mistake.

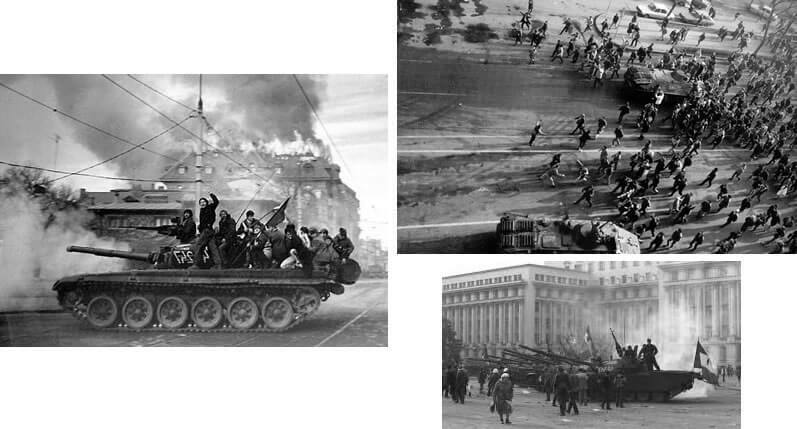

The army is not a "tool" to be used in subtle ways, and at dusk on the 17th, Timisoara looked like the logical thing to do after a military intervention: a battlefield.

Armored vehicles had been used, shots had been fired, there had been deaths, but, above all, the civilians had been emboldened and had faced the military. You have to be very desperate and ready for anything to confront, almost with your bare hands, those who have rifles. And the Romanian citizens were.

After two more days of fighting, on the 19th the workers marched through the city, joining the movement anti-government, which turned the protest into an unmitigated rebellion.

Over a hundred thousand workers stood up to the army and the security forces, a figure that the regime forces could not handle without provoking a great bloodbath.

The same regime, led by Nicolae Ceaucescu's wife, Elena (her husband was on a diplomatic tour in Iran) sent workers from other areas of the country, armed with clubs, to confront the revolted workers without having to resort to the army, a shot that came out of the butt.

Persuaded that they were going to confront violent elements of the Hungarian minority in the country, which together with the uncontrolled were endangering the territorial integrity, the Newly arrived workers saw that what they had been told was a lie and that, before them, they had others like them with the same disgust for the regime and their own claims.

This being the case, the arriving workers joined the revolt, increasing the number of those who clamored for the end of the Ceausescu dictatorship in the country, and calling on the soldiers to be join.

Seeing the course that events were taking, Nicolae Ceausescu hastily returned his tour of Iran to take the necessary measures to end the revolt.

Among these, the conductor he wanted to make a public speech from the large balcony of the Communist Party of Romania headquarters on December 21. The image that was found, broadcast and repeated ad nauseam on television, was that of an audience protester who did not let him speak, rebuked him, and launched a slogan in favor of the mutineers of Timisoara.

The revolution had not only spread to Bucharest, but the whole country had seen that the dictator could be faced and to his repressive apparatus: in his attempted speech, stunned, Ceausescu had to leave him halfway and they had to make him enter the building for fear of some attempted physical aggression by throwing objects, which was extremely difficult, but not impossible.

All of Romania, and the world, saw the unequivocal sign of the end of the regime, and the citizens knew how to get the message and lost all fear; that same morning the taking of Bucharest began.

It was in Timisoara, and then it spread to Bucharest, where the symbol of that revolution emerged: the Romanian flag with a circle-shaped cut in the middle, thereby eliminating the communist shield where previously there was condition.

In the capital, clashes took place between the revolutionaries and the army supported by various units of the Securitate and police, a real street battle that the troops seemed to have controlled during the morning of 22 December.

Once again it was the masses of workers, who came from the outskirts of Bucharest, who decided the situation.

Unable to contain the flood of protesters, the armed forces began to break down, and many soldiers (who were affected by the regime disliked as much as those they were supposed to suppress) began to join the uprising and organize to protect the crowd.

The revolt followed the clear patterns of other popular uprisings, such as the French Revolution or the Russian, in which at a given moment, the soldiers see the situation so clear that they decide to go over to the side of those they see as victors, since the troop is also part of the most unprotected classes (leaving aside the officers), and they see that there will be no reprisals against them or their families since the regime they protected until now is going to fall.

After another attempt at public discourse that could not even begin, Ceaucescu and his wife fled, seeing the situation lost.

The flight of the dictator and his wife was facilitated by Víctor Stanculescu, whom Ceaucescu had appointed minister of defense. Politicians close to the dictator began to think about sacrificing him to stay alive.

After the flight, the crowd took the headquarters of the Communist Party and marched freely through the city, celebrating the victory together with the soldiers, who were now on their side. However, and with troops still loyal to the old regime, this soon degenerated into urban battles that would throw, over the next hours and days, a balance of some dead.

The National Salvation Front (FSN) took power in Romania, an organization born of prominent members of the Communist Party who, make no mistake, were trying to save his skin.

While all this was happening, the Ceausescu had arrived by helicopter to Tirgoviste, a city located in the center of the country, from where they could not continue because the country's airspace had been closed. There, in Tirgoviste, they were detained by the police and taken to a military barracks.

On December 25, 1989, Christmas Day, Nicolae Ceaucescu and his wife Elena were tried, sentenced to death, and the sentence carried out, in a kind of "express trial" that left more open questions than answered.

The main one: why this speed? Earlier I said that it was necessary to measure to what extent the revolution was really popular, and in the most probable answer to this question we can find the cause of the doubt.

In a conventional trial, with its tempos much slower, the Ceausescu, both he and she, could have dumped accusations on the FSN leaders who had been members of the old regime, which obviously did not interest these.

So to liquidate the Ceaucescu quickly amounted not only to saving skin, but also to being able to play a role in the country's political future, and that is possibly what happened.

The images of the corpses of the Ceaucescu went around the world.

The transition from communist governments had been peaceful throughout Eastern Europe (the violent disintegration of Yugoslavia), Romania being the only country in which this process practically caused a civil war.

Themes in the Romanian Revolution of 1989