Definition of Lateran Pacts

Miscellanea / / July 04, 2021

By Guillem Alsina González, in Dec. 2018

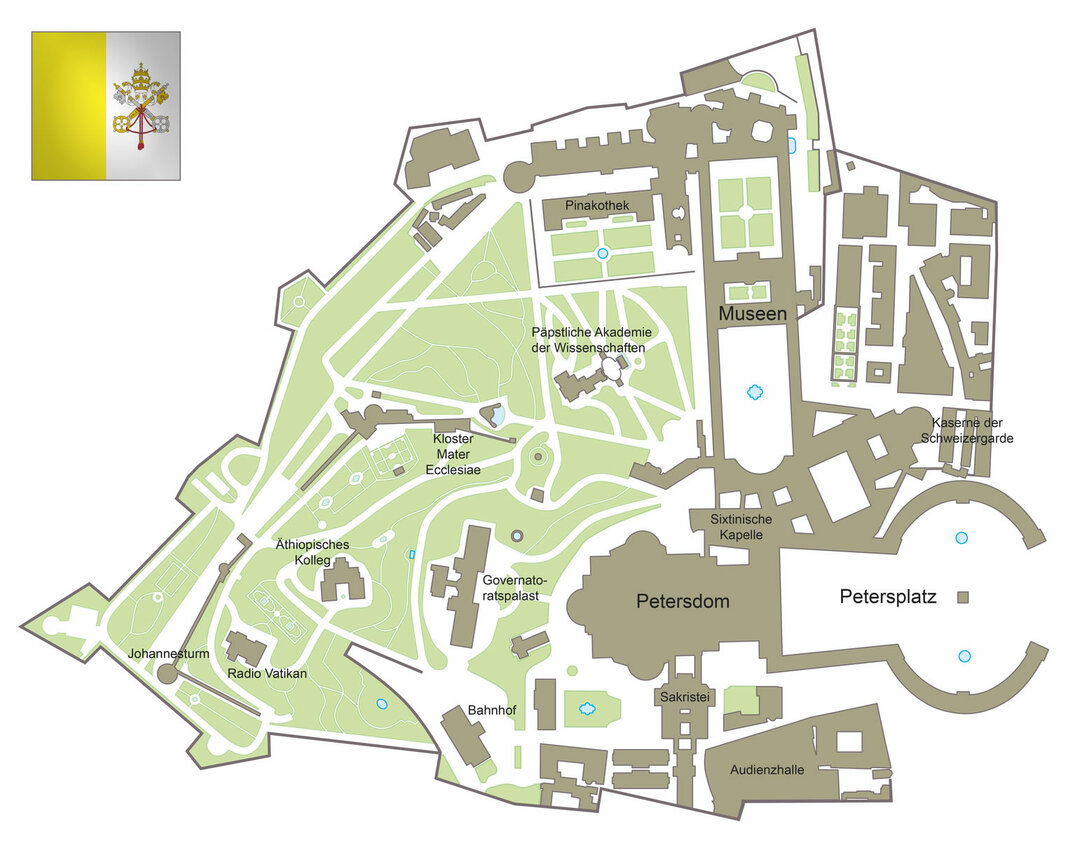

One of the points of greatest interest in Rome is for a triple reason: historical, religious and tourist. With this definition, surely you have already guessed that we are talking about the Vatican, a small state (in fact, the smallest in the world) that inhabits the heart from the city of the Caesars.

One of the points of greatest interest in Rome is for a triple reason: historical, religious and tourist. With this definition, surely you have already guessed that we are talking about the Vatican, a small state (in fact, the smallest in the world) that inhabits the heart from the city of the Caesars.

While it has borders (and, perhaps, the most clearly delimited in the world: a white line that surrounds its limits, at least in part from the Plaza de San Pedro), to cross them you do not need to present your passport or any other document, just keep walking from Italy.

The tourist who is not attentive, surely will not even realize that he has changed country, although being aware of the fact, if he does not know the history, he may think that the fact that the Vatican is independent must be a concession from Italy to the Holy See.

Nothing is further from the truth, and Italy and the Vatican only recognized each other at the end of the twenties of the twentieth century.

The Lateran Pacts were a series of agreements signed between the Vatican and the Kingdom of Italy in early 1929, by which the Holy See recognized the state of Italy and vice versa.

How could this situation have occurred if Italy is one of the countries whose population have greater Catholic religious fervor? To understand it, we must go back to the process of unification of the Kingdom of Italy, which culminated in 1870 with the absorption of the Papal States.

The latter were the earthly possessions of the papacy, which occupied the central portion of the Italian Peninsula, and whose capital was in Rome.

It is still curious to think that before 1870, Rome was not part of Italy and that, in fact, it was thought to establish the capital of the new country in Florence, the cradle of the Renaissance.

Rome was occupied on September 20, 1870 by Italian troops as part of the unification of that country.

Although, in fact, the Papal States were an entity politics in decline since 1848, and from 1860 possessed little more than the city of Rome itself and its environs. The outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 would lead to the withdrawal of the French garrison that protected the Pope, and an Italy allied with Prussia that would have carte blanche to annex the city eternal.

On May 13, 1871, the Italian government approved the Papal guarantees law, a first attempt by the nascent Italian state to regulate relations between it and the Holy See.

Said text established a regime of extraterritoriality for the papal dependencies (what would become today Vatican City), the recognition of the pontiff himself as head of state and the treatment given in accordance with that honor, that he could have a armed corps (the Swiss Guard) at his service, and the Vatican's ability to receive foreign diplomats and appoint his own own.

Said text established a regime of extraterritoriality for the papal dependencies (what would become today Vatican City), the recognition of the pontiff himself as head of state and the treatment given in accordance with that honor, that he could have a armed corps (the Swiss Guard) at his service, and the Vatican's ability to receive foreign diplomats and appoint his own own.

Is law it was not accepted by Pope Pius IX, who declared himself a "prisoner in the Vatican" and also refused to recognize the new Italian state. However, the Law of guarantees it worked unspoken.

The atmosphere is not good, and the church goes so far as to prohibit Italian Catholics from entering politics in the new state, as revenge against the "occupiers" of Rome.

It was Benito Mussolini who, once in power (from 1922), put the agreement with the papacy on the Italian political agenda, although this did not arrive until 1929.

Mussolini had arrived eager to consolidate a power achieved through a coup d'état and to assert himself before the Italian people, so the entrenched conflict with the Holy See seems an excellent opportunity to do so.

It was Mussolini himself, on behalf of the King of Italy Victor Emmanuel III, who negotiated on the Italian side. His ecclesiastical counterpart was Cardinal Pietro Gasparri. The agreement was signed on February 11, 1929.

There are three Lateran Pacts: recognition of the sovereignty of the Vatican, regulation of relations between it and Italy, and financial compensation to the Holy See for its losses.

The first is easy to understand, and enters into the usual dynamics between countries: one and the other recognize each other and establish diplomatic relations. To date, neither of them recognized the other.

The second pact, the concordat between both states (after the Spanish Civil War, the Franco regime also would sign a concordat with the Catholic Church) is already more complicated, and is the answer to the question of how find a Balance between the interests of both.

Thus, the Holy See guaranteed that the members of the Italian church would not get involved in politics (something that was of great interest to Mussolini) and that they would even swear allegiance to the state. In return, the Italian fascist government made the teaching of the Catholic religion compulsory in school, and accommodated the marriage and divorce law to the canons dictated by the church.

Let's say it was an arrangement in which both parties gave something to come to a mutual agreement.

The third agreement was, basically, an economic reparation for the territorial (and, therefore, patrimony) losses of the church in 1870.

The succulent amount that the Vatican got from this third agreement allowed it, in 1942, to create its own bank, the Banca Vaticana (officially Institute for Works of Religion, which continues to exist today, and which was involved in controversy in the late 70s and early 80s of the 20th century over the Banca Ambrosiana scandal.

The pacts are still in force today with modifications, such as that of 1984, which led to the abandonment of Catholicism as religion of the state and opened the door to the entry of other religions in the classrooms, such as Judaism or Protestantism.

While the Second World War, the defeat of Italian fascism, and later the expulsion of the family Italian royalist and the conversion of the country into a republic, could have substantially modified or even ended the pacts, these were included as part of the Constitution Italian from 1948.

They consist, in particular, in Article 7, which eliminates the possibility that Italy can abolish them unilaterally, thereby guaranteeing the maintenance of the state of the Vatican.

Photos: Fotolia - Panda / Kartoxjm

Themes in Lateran Pacts