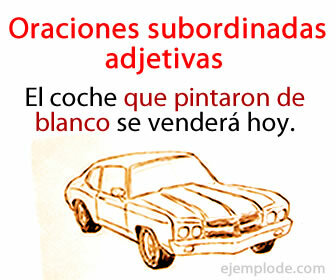

Gallic war

Miscellanea / / July 04, 2021

By Guillem Alsina González, in Jan. 2018

It is one of the most famous and studied conflicts of antiquity, and it was the scene where the legend of a Roman general and politician whose footprint we can still see patent in our society today: that of Julio Cease. It was the Gallic War.

It is one of the most famous and studied conflicts of antiquity, and it was the scene where the legend of a Roman general and politician whose footprint we can still see patent in our society today: that of Julio Cease. It was the Gallic War.

The Gallic War was the armed conflict that faced the Roman Republic represented on the one hand by Julius Caesar and, on the other, a coalition of Gallic (Celtic) tribes led by the leader Vercingetorix.

However, we could well speak of a confrontation between Caesar personally, taking advantage of his position as governor of the two Gallic provinces, the Transalpina and the Cisalpina, and the coalition gala.

Julius Caesar's coffers were empty and the leader in debt, having spent more than he had to boost his career politics to the consulate; This was a common practice among the Roman political class, since they knew that the same commands obtained, or later, would allow them not only to pay their debts, but also to enrich themselves.

Many of these practices would today be considered outright corruption.

After the consulate, Caesar obtained the government of the provinces of the Gala Cisalpina and Iliria, to which he added the Gaul Transalpina when the governor of the latter died unexpectedly before even being able to leave for said Province.

The risk of armed confrontation in the area was high, and the Roman Senate knew it; Caesar's appointment was therefore not gratuitous.

The Gauls, in turn, were under pressure from the Germanic tribes, which led them to come dangerously close to territory Roman.

The fire was opened by the Helvetii, a very powerful tribe, which he decided to carry out, in 58 BC. C. a massive migration over Roman territory.

Earlier, the Helvetii sought alliances with various other Gallic tribes. The Romans also had allies among the Gallic tribes, and some had already begun to be Romanized, that is, to adopt Roman culture by merging it with their own and with their traditions.

The Helvetii had arrived in the region where the city of Geneva is currently located, and they tried to force the passage of the Rhone River.

His attempts were rejected, so they sought an alternative route. Leaving a fortified legion guarding this pass, Caesar recruited two legions that he added to the other three of the four that he had under his command, and set out in pursuit of the Helvetii.

Historians have long argued whether this movement corresponded to a strategy to stop that tribe, or else Caesar was causing a conflict larger for their own benefit.

The Helvetian tribe passed through the lands of various other Gallic tribes, sometimes in an agreed and peaceful way, and other times rampaging and looting. The tribes affected by these looting, powerless, requested help from the Romans who were pursuing the Helvetii.

Dumnorix, of the Eduos tribe, made it difficult for the Roman troops to get supplies, which led to that the situation was reversed, placing the Romans in the position of persecuted, and the Helvetii as pursuers.

So the Romans decided to eliminate the Eduos from the game, attacking the oppidum of Bibracte.

In this battle, the Romans crushed the Helvetii, forcing the survivors to return to their territory.

From here, the Gauls allied with Rome requested help from Caesar to combat the Suevian threat.

The Suevi were a Germanic tribe who had entered Gaul as mercenaries, and were causing riots. Caesar sought the confrontation with them by declaring friend and ally of the Gauls.

Near the fortified city of Vesontio (belonging to the Sequoia tribe), Caesar fought a successful battle against the commanded Suevi by Ariovistus, which resulted in the remaining Suebi on the other side of the Rhine refusing to cross it to continue their invasion of the Gaul.

The next conflict was with the Belgians.

This tribe had attacked Gauls allies of Rome, so Julius Caesar intervened with his legions, defeating the Belgians, although he was about to lose.

From here, and in 56 a. C, Caesar launched a campaign against the tribe of the Venetos, on the Atlantic coast of present-day France.

This was a tribe that dwelt on the Armorica peninsula (where Uderzo and Goscinny place the adventures of Asterix ...), in Britain, and whose power resided in his fleet, which led the Romans to have to build another and attack them by land and sea.

After defeating them, Caesar would turn again to the Germans ...

On this occasion, it was the tribes of the Usipetes and the Tencteri that carried out a massive migration over Gallic territory, and to whom the legions of the future dictator blocked the way.

As with the Helvetii and in so many other cases of the ancient world, the Romans used the natural accident provided by a river to stop the advance of the Germans and adopt defensive positions, in this case the Meuse.

Again, the Roman general won victory, putting the survivors of both tribes to flight.

To definitively avert the German danger, Caesar decided to carry out a punitive expedition to his territory.

So, building a bridge over the Rhine, he entered Germania with several legions, but did not get to fight because the different Germanic border tribes shunned it, chastened by the failures of previous forays into the Gaul.

In 55 a. C, Caesar carried out a raid in Britannia (present England).

However, in this case he could not - or did not know - to consolidate the conquest, and had to retire the following year.

Of course, the campaigns against the Gauls and having come to defeat the exotic Britons on their own soil, earned Caesar great fame in Rome.

What the Roman politician did not expect was that upon his return to Gaul ...

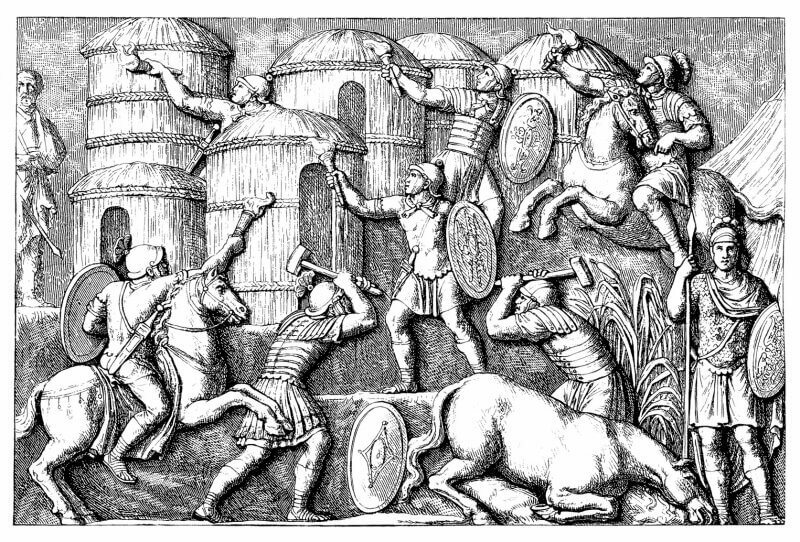

Fed up with Roman rule, the Gauls had plotted revolts against the occupiers. the first were the Eburones.

These were a Belgian tribe that, at the time of rebelling, were able to annihilate the Roman troops of the region, but they were quickly put down by Caesar in command of the legions that had returned.

It is, after this campaign, that the most epic and well-known episode of the Gallic War begins, and that everyone associates with this conflict: the uprising of Vercingetorix.

Vercingetorix was a Gallic chieftain of the Arverni tribe, who in 52 BC. C. he managed to unite under his command the Gallic tribes to face Caesar.

Only one initially refused to be part of the alliance of tribes against the Romans, the Eduos, although later they would change sides.

Only one initially refused to be part of the alliance of tribes against the Romans, the Eduos, although later they would change sides.

Vercingetorix decided to use a tactic of simultaneous uprising throughout Gaul, coupled with a "scorched earth" policy, consisting of destroying everything that could serve the Romans (such as supplies) in their wake, so that the enemy troops soon suffered from a shortage of everything, starting with the food.

That same tactic would be used later in several wars, especially on the eastern front in the USSR in full Axis advance during World War II.

Caesar's luck was that the Bituriges, one of the revolted Gallic tribes, refused to burn their capital, which was taken by the Roman general's troops.

This was a severe blow to the Gauls, who were aware of the Roman tactical and strategic superiority, and who hoped to force them to retreat in order to attack them on their own territory.

Vercingetorix then withdrew with his troops to Gergovia, the capital of the Arverni.

Gergovia would constitute a moral victory for the Gauls, although in reality it was more of a “technical draw”. Gergovia would lead directly to the end of the contest: the siege of Alesia.

After not being able to take Gergovia, saved by its walls (and the uncoordinated action of the forces Roman), Caesar went after the Gallic army, and some skirmishes broke out in the course of the persecution.

Vercingetorix thought that Alesia (capital of the Mandubios) would allow him to defend himself as in Gergovia. But the Roman troops had learned from their mistakes and, under Caesar's orders, they built a double stockade around the fortified city.

The inner palisade surrounded Alesia and prevented the escape of those surrounded, while the outer one protected Caesar's legions from attack by Gallic forces from outside.

The situation within Alesia soon reached an untenable point; under Vercingetorix's orders, the besieged drove out the women, the kids and those who could not fight, from the fortress, with the intention that these would be saved by Caesar at the cost of the supplies of the legions.

But the Romans did not fall into the trap, leaving the most defenseless beings in no man's land between the walls of Alesia and the Roman interior stockade.

The Romans were attacked by Gallic forces abroad, although they were able to resist well thanks to the auxiliary camps they had set up along their perimeter.

Seeing himself defeated, Vercingetorix decided to surrender. The last Gallic hope of freedom ended in Alesia.

The next two years, Caesar's troops were spent carrying out “cleansing” operations from minor rebellions and pockets of resistance.

Vercingetorix was taken as a prisoner of war to Rome, participating, five years later, in the parade triumphant Caesar, after which he was executed by the method of strangulation in the prison of the Tullianum.

The Gallic War marked the beginning of the end of the civilization Celtic in present-day France, beginning the cultural fusion with Roman civilization.

Photos: Fotolia. Erica Guilane-Nachez / Jay

Themes in Gallic Wars