Definition of Achaemenid Empire

Miscellanea / / July 04, 2021

By Guillem Alsina González, in Jun. 2018

When we mention the great empires of antiquity, a name quickly comes to mind: Rome. And secondly, maybe Greece, really thinking of Alexander the Great's Macedonia bathed in classical Greek culture.

When we mention the great empires of antiquity, a name quickly comes to mind: Rome. And secondly, maybe Greece, really thinking of Alexander the Great's Macedonia bathed in classical Greek culture.

But at the crossroads of civilizations that has been the Middle East, there is another empire, often forgotten, that also astonished - and conquered - the world until the aforementioned Alexander the Great finished him off: the Empire Achaemenida.

The Achaemenid Empire was the first empire founded by the people of the present Republic of Iran (the Persians).

Its name is given by the one who was its mythological founder, Aquemenes (at least, it has not been possible to verify the real existence of this character).

The Greeks knew the Persians as Medes, and this has their reason: initially, Persia was a tributary of the Median Empire... until his strength was such that he ended up conquering that empire.

The ability of the Achaemenid Persians to keep the conquered states within their political-social structure was remarkable.

Unlike other colonizing powers that history would see a posteriori, when the Achaemenid Empire absorbed a kingdom, it did not impose its religion nor his language, although if it did so with its bureaucratic structure and administrative, seeking, yes, to keep a local nobleman at the head of the organization.

These nobles received the name of satrap, a name that has happened, at present, to unfairly denominate whoever acts in command in a dictatorial way. Although, certainly, the government of the satraps he was personalistic and despotic, he was no more so than many other leaders of other cultures of the time and later.

The King of kings (title held by the Persian sovereign) was also entitled with the royal office of the conquered country. In Egypt, for example, he was pharaoh.

This did not prevent riots from taking place in various territories, as in the case of Egypt, but in general caused the conquered populations to be satisfied by being able to continue making their lives normal.

It is also true that, normally, at each change of monarch, the incoming king had to deal in the first place with pacifying the Empire due to the revolts that he had caused. change, since sometimes different nations within the Empire supported different candidates for the throne or simply took the opportunity to try become independent.

A good example of this policy was the absorption of the Greek cities of Ionia (on the current coast of Turkey), when the Achaemenid Empire conquered the Kingdom of Lydia.

These cities, tributaries of Lydia, enjoyed the same autonomy and even more, under Persian imperial sovereignty, until they were incited to rebellion from Greece. This rebellion was crushed with blood and fire because, if there was something that did not tolerate the hierarchy of the Empire, this was rebellion.

The model of assimilation of the territories was also produced in the army.

Thus, each unit from each of the countries that made up the Empire, entered to fight with its uniform and its panoply This did not prevent the existence of technological exchanges in the field of weapons between the peoples that made up the Empire.

Following the absorption of the Median Empire, the nascent Achaemenid Empire launched itself upon the Neo-Babylonian Empire.

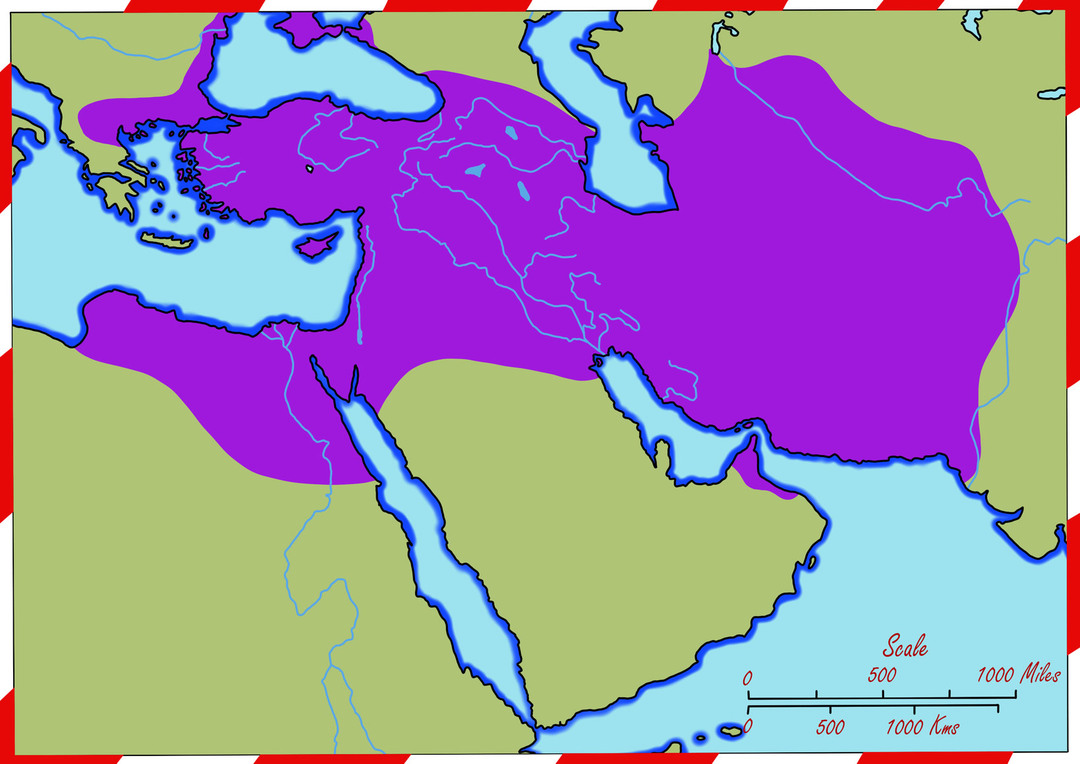

After this, the Achaemenid Empire expanded in two directions, east and west; for the first, it would reach in its maximum splendor to the Hindu Kush mountain range, in present-day Afghanistan, while to the west, it would reach the Mediterranean, conquering Asia Minor and Egypt.

Territorial expansion reached its culmination with the annexation of Thrace, which allowed Persia to set foot in Europe. But, from here, the first military failures arrived.

The most famous of all are perhaps the Medical Wars against the Greeks, which slowed the expansion of the Achaemenids, but a lesser known and just as vital defeat was against the Scythians, a confederacy nomadic peoples that inhabited the Caucasus area and the coast north of the Black Sea.

The Scythians practiced a politics of "scorched earth" that greatly hindered the movements of the great Persian army, which in the end had to return to its starting point since it could not stay on the ground.

Despite these defeats, and also despite a series of losses and recoveries of different territories (Egypt was Persian on two occasions, temporarily achieving the independence), the Achaemenid Empire survived, but only until the irruption of Alexander the Great.

Drawing on the power established by his father, Philip II of Macedon, and also on his idea of conquest of the Persian Empire, Alexander the Great assembled an army of Macedonian soldiers and Greek allies and, in 332 a. C, he set out to conquer the Achaemenid Empire.

After a series of victories (Isos, Gránico, Gaugamela), the Great would complete the conquest of the territories of the Achaemenid Empire, annexing it in a way that he had learned from the Persians themselves: leaving local rulers in command, in some cases the same satraps who were already in the days of the Achaemenids.

Alexander himself also adopted some traditions Oriental Persians, to the chagrin of their own, who saw them as barbarian customs ...

To the Aqueménida Empire it would happen to him, after the death of Alexander in 323 a. C, the Seleucid Empire (for Seleucus, one of the Great's companions) and, after this, the Empire Parthian, which would precede the Second Persian Empire, the Sassanid Empire (by the name of their dynasty reigning).

Photo: Fotolia - Keith Tarrier

Themes in Achaemenid Empire