Definition of Dreyfus Case

Miscellanea / / November 13, 2021

By Guillem Alsina González, in Oct. 2018

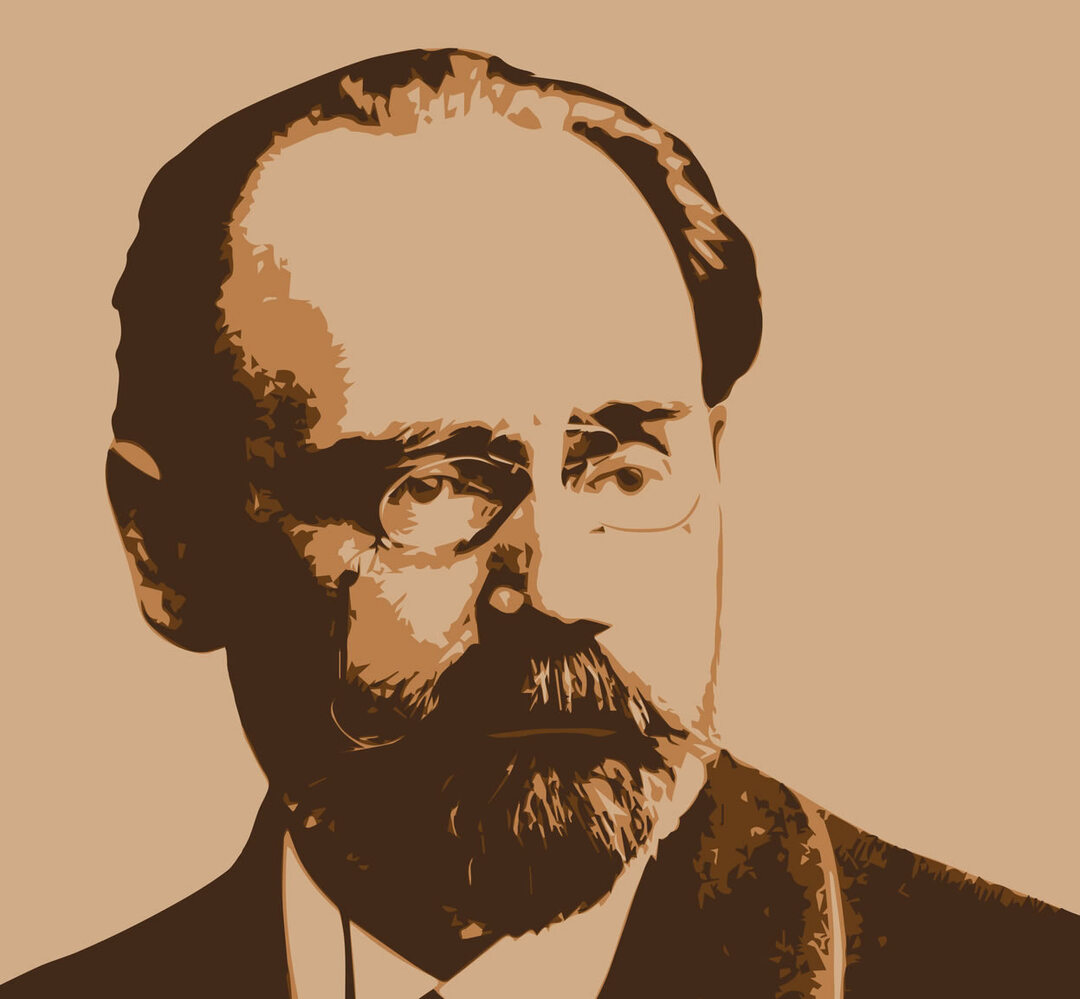

"I accuse!", In reference to the title of the famous article by Émile Zola, is one of the most repeated quotes in the world when talking, regularly, about political issues. but who and why was the French writer accusing?

"I accuse!", In reference to the title of the famous article by Émile Zola, is one of the most repeated quotes in the world when talking, regularly, about political issues. but who and why was the French writer accusing?

The so-called “Dreyfus case” consisted of a judicial process against a French military man (Alfred Dreyfus) falsely accused of espionage, but the most important thing is that he demonstrated the anti-Semitism and revanchism against Germany prevailing in society French.

Since 1892, the French espionage counterintelligence department (the Section de Statistique) knew that the military attaché of the German embassy in Paris, Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen, carried out espionage actions on Gallic soil.

And this he knew thanks to the woman cleaning the embassy who was, in fact, an informant for the Section de Statistique who collected the waste from von von Schwartzkoppen and took them to the French counterespionage service offices, where the pieces of paper were analyzed and meticulously joined to end up forming documents. originals.

This is how, in 1894, an alarmed civil servant discovers that von Schwartzkoppen has an informant from inside, which has sent you a list of sensitive French military documentation to which you can to access. This list will be known by the name of borderreau (A word that, in French, is used to describe an exhaustive list, such as a ship's manifest).

The document came into the hands of Major Hubert-Joseph Henry who apparently did not want to recognize the handwriting - it was later claimed, easily distinguishable- handwritten by a good friend of his, who would be the German agent, “entertaining” the report before making it reach his superiors of him.

From here, and instigated by Henry, the investigators mistakenly searched for a suspect where he was not. And so they came across one that was perfect for exploiting the deepest prejudices of Gallic society at the time.

Captain Alfred Dreyfus was born in 1859 in Mulhouse, Alsace, one of the regions that Germany had taken from France after defeating it in the Franco-Prussian War (which gave rise, precisely, to the birth of the German Empire), and professed the faith bean.

Antisemitism and revenge in the face of the eternal German enemy were thus combined in a character who served as a scapegoat. And so, on October 15, 1894, Dreyfus was arrested as a suspected spy in the service of Germany.

What followed was not a trial, but a public lynching that opened the thunder box in French society, exposing its shame.

The investigation it had been carried out in a biased way; to get to the conclusion that it could be Dreyfus, he had decided investigate to some general staff officer linked to artillery, only because in the bordereau there were some mentions of artillery documents (as there were those of other arms), although terms were overlooked that a staff officer would not mention in the terms mentioned.

The strongest evidence that the prosecution should have had was that of the calligraphic comparison, which It was not made by experts, and that it was only based on a very sui-generic resemblance of both scriptures.

In fact, the so-called expert (who was not a calligraphy expert), Alphonse Bertillon, created a theory that conformed to the facts and not to the the other way around (that is, the facts should have squared the theory): that Dreyfus would have imitated his own writing "to mislead."

By the way, some of the researchers (and I'm giving them that nickname to do them a favor) were openly anti-Semitic. And Dreyfus was the only Jewish officer on the staff at the time ...

Although at first it was sought to keep the case secret, this became known to the public from the leak made of it by the anti-Semitic newspaper The Free Parole.

The newspaper was tendentiously anti-Dreyfusian for being anti-Semitic, and it continued to set this trend throughout the case. The media, like society, was fractured between Dreyfusians and anti-Dreyfusians.

The investigation and the trial itself focused on evidence that, in reality, consisted of nothing more than at most today we would call circumstantial or, directly, they should never have been admitted, in any context, as tests.

Apparently, and according to witnesses, Alfred Dreyfus had a good knowledge of the German language, something logical for someone born in Alsace, in which a dialect variety of the German is spoken. German, in addition to the fact that French officers were rewarded for their knowledge of German (Germany has been, together with England and Spain, one of the historical enemies of France). But knowledge of the language was an indication of guilt for the prosecution.

Likewise, Captain Dreyfus was gifted with a prodigious memory... that could help you remember the information that you would later pass to the intelligence German. Faced with this strange argument, the only possible reaction is the modern WTF!

The lack of material evidence was explained, in the maximum delusion of the prosecution, as incriminating evidence in itself, since the captain had eliminated everything ...

Thus, following this reasoning, it is to be assumed that an innocent person, something should be found... Or in this case he would be guilty? No, obviously, this reasoning has neither head nor tail.

Meanwhile, in the written press there was a scuffle between anti-Dreyfus and favorable media, with inflamed editorials and articles. What today we would call fake newsSlanderous articles with falsehoods about Dreyfus's life were commonplace in the anti-Dreyfusian media of the time.

The process suffered from abuses against Dreyfus and his defense, which, even then, were out of the law and intolerable.

This is exemplified in the delivery of documentation to the judges that could not be reviewed by the defense, contravening any spirit of equality before the law and impartiality of this. Those who had orchestrated this witch hunt were demanding Dreyfus's head no matter what.

Alfred Dreyfus defended himself vehemently, dismantling point by point and with logical arguments, the accusations. But with everything against it, the mission not to prove his innocence, but to believe it, was impossible.

On December 22, 1894, Alfred Dreyfus was found guilty of high treason and sentenced to be demoted (from his military rank), expelled from the army, and to life imprisonment in a prison outside of France continental.

Dreyfus was publicly demoted for further derision, and taken first to a prison in Guyana and then to Devil's Island. Just from the name, we can already imagine that it was not exactly a resort in which to relax, but a harsh private prison of the most basic elements for a minimum well-being.

And to the conditions, already harsh, must be added a brutal behavior of their jailers.

But although this "match" had been lost, the tie was not, there was still the "second leg".

Mathieu Dreyfus, Alfred's older brother, was the one who began to investigate on his behalf despite the threats received from military sectors, reaching the secret document that the prosecution had shown to the judges.

Little by little, the conspiracy that had loomed over Dreyfus was being shelled before the public through the newspapers, and the reverse Definitive to the accusation was the change of the head of the Section de Statistique, Colonel Sandher, by Lieutenant Colonel Georges Picquart.

The latter, who had followed the case with interest, discovered a document addressed to the real spy who had infiltrated the French army, which left the case against Dreyfus completely out of the question.

And who was the friend of Major Hubert-Joseph Henry whom he protected and whom Picquart discovered?

Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy, a French military man with roots in the Hungarian aristocracy, who had come to work, paradoxically, for Gallic intelligence in his counterintelligence section was the spy, acting motivated by money due to his numerous and bulky debts.

The calligraphy of the Bordereau list perfectly matched Esterhazy's handwriting.

Before the requests for review of the case, the French general staff refused to not admit the error, preferring to take carry out a separate process against Esterhazy and maintain the sentence to Dreyfus, under the premise of "case tried, case closed". Picquart was even "banished", assigning him to colonies so that he would "stop bothering".

Henry also participated in the concealment of the error by fabricating a false evidence against Dreyfus, consisting of an alleged letter (never really existing) sent by the military attaché of the Italian embassy to his namesake of the German, indicting Dreyfus.

The high command and all those directly implicated in Dreyfus's conviction feared discovery, and were doing what was necessary to hide the plot and further implicate Dreyfus. Having a secret archive allowed them to manufacture tests as they were needed.

But the avalanche was upon them: in 1897, the dreyfusards they learned of the identification of Esterhazy's handwriting with that of the list held by the German military attaché.

Mathieu Dreyfus filed a complaint against Esterhazy with the French General Staff, making the scandal public and leaving no choice but to open an investigation.

Influential journalists and writers, such as Anatole France, Paul Bourget and, above all, Émile Zola, will publicly embrace the Dreyfusist cause, as well as convince politicians such as Léon Blum.

Influential journalists and writers, such as Anatole France, Paul Bourget and, above all, Émile Zola, will publicly embrace the Dreyfusist cause, as well as convince politicians such as Léon Blum.

But even so, the staff still refused to reopen the case and even seemed to want to save Esterhazy by sacrificing Picquart.

This was confirmed by the Esterhazy trial, which did not save any legality in the forms, and in which the accused ended up being exonerated, while Picquart was accused and purged without being guilty of anything other than making the truth known.

It is in this climate that, as early as January 1898, that Émile Zola signed his famous J'accuse, an article in which he makes explicit and denounces, with names and surnames, the plot against Dreyfus.

And guess what those involved did? Indeed, denouncing Zola for defamation, which only managed to put the Dreyfus case in the eye of the public opinion and the center of debate. Zola defended himself with brilliant rhetoric by counterattacking and explaining details of the Dreyfus case.

Why? Simple: the Alfred Dreyfus trial had been held behind closed doors, so the public opinion did not know its details.

Thanks to the trial of Zola, the public learned about the entire conspiracy, by the details of the trial of the writer that became known to the press.

Finally, Zola was sentenced to a year in prison and the payment of a large fine, and he ended up going into exile in England for a short period of time, because in France his safety staff was in danger.

Elections were also held in 1898, and it will be the new minister of war, Godefroy Cavaignac, who will discover the assembly of the incriminating evidence against Dreyfus, paradoxically when he tried to definitively prove his guilt, since he was antidreyfusian.

In the interrogation to which he subjected Major Hubert-Joseph Henry, he ended up confessing the entire assembly. He would be immediately taken to prison, where he would commit suicide the next day. And Cavaignac resigned.

There was no choice but to review the trial. And, meanwhile, Alfred Dreyfus was unaware of all this reality and the struggle that half the country was carrying out against the other medium so that his innocence would be recognized.

On June 3, 1899, the court of cassation annulled the sentence of 1894 and led to the opening of a new court martial. Dreyfus was transferred from Devil's Island to Rennes military prison in mainland France.

However, in the new trial he would also be found guilty, although he was given a sentence of "only" ten years thanks to extenuating circumstances. Defending him, he would continue without giving up total acquittal. The process was again adulterated, nullifying the confessions of Henry and Esterhazy, something unheard of.

At the end of the same 1899, Dreyfus is offered a presidential pardon, which although he was reluctant to accept, he will end up doing it in order to reunite with his own.

Although this disappointed his supporters, it is necessary to understand what the poor man had suffered between the accusation, the two trials and the prison. At least now, he could live in freedom.

Nevertheless, Alfred Dreyfus was a man of honor and, seeing this staining, in 1903 he requested a review of his case.

The case will be studied again between 1904 and 1906 in a meticulous way and, finally, in 1906 Dreyfus will be rehabilitated (as well as Picquard) and readmitted to the army. The same year he will be made a knight of the Legion of Honor.

And how did Esterhazy end up? For exile in England, he ended his days there, without pain or glory but evading the French justice in freedom.

One might think that, after the treatment received by "the fatherland", Dreyfus would not have wanted to know anything more about France. Well, as a good patriot, and without resentment to the country itself (although we can assume what he should think of who accused him unjustly), Dreyfus did not hesitate to enlist in 1914 to fight in the new war against Germany.

The Dreyfus case Not only did it uncover the anti-Semitism and violent nationalism within French society, but it also stressed that society to the extreme of a weather pre-war civil war, in which there were even anti-Semitic altercations.

Seldom has a trial attracted so much attention and tension. But it is that few times justice had been bent to such an extreme.

And France is still marked by the case; I do not remember exactly when it was, but I remember seeing an accusation in the French National Assembly as a young man. It should be in the 80s, almost a century after everything happened ...

Fotolia photos: Rider

Themes in Dreyfus Affair