Definition of Battle of Pydna

Miscellanea / / July 04, 2021

By Guillem Alsina González, in May. 2018

It marked the end of the Macedonian monarchy heir to one of Alexander the Great's generals, as well as signifying the final defeat of a training military that had become legend: the phalanx made up of spearmen. The Battle of Pidna also meant the beginning from the end of free Greece, which came to orbit completely around Rome.

It marked the end of the Macedonian monarchy heir to one of Alexander the Great's generals, as well as signifying the final defeat of a training military that had become legend: the phalanx made up of spearmen. The Battle of Pidna also meant the beginning from the end of free Greece, which came to orbit completely around Rome.

The Battle of Pidna, which sealed the fate of Macedonia in the Third Macedonian War, was fought on June 22, 158 BC. C, and faced on one side the troops of the Macedonian kingdom, and on the other the legions of the Roman Republic.

The battle was more than an armed confrontation, since it marked the end of the Macedonian kingdom, which would later be divided, and also meant the debacle of the old tactic of the Macedonian phalanx against the mighty Roman legion, a more versatile formation that could be worked with more during the battle.

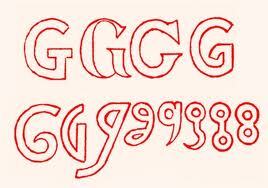

The Macedonian phalanx was somewhat different from that which the Greeks had devised based on hoplite fighting, although did not cut with this: deriving from the hoplitic phalanx, Philip II (father of Alexander the Great) had lengthened the spear (called

sarissa) down to seven meters, and had revamped tactics into a virtually invincible formation that his son skillfully used to defeat the Empire Persian.And so it was considered, as invincible, the Macedonian phalanx until the defeats of Cinoscéfalos first (197 a. C, Second Macedonian War) and Pidna later.

The Battle of Pydna, which was fought near the city of the same name, was triggered by a retreat to the north of Perseus, king of Macedonia, to avoid being attacked in a pincer movement on two fronts by the Romans.

The Macedonian monarch arranged his troops in a plain, appropriate terrain for the formation of the phalanx. Meanwhile, the Roman consul Lucio Emilio Paulo joined the two fronts of his troops to present battle.

Paulo acted cautiously, placing his camp in the skirt of a Mountain nearby, thus preventing a surprise attack by the Macedonians with their phalanxes, since this was not an appropriate terrain to use such a formation.

In total, in the plain of Pidna some 44,000 soldiers were deployed on the Macedonian side, including infantry and cavalry, while on the Roman side between 30 and 40,000 men did so.

Legend has it that the battle was caused by a mule.

It is unknown if it was a Roman ruse (said mule seems to have escaped from the Roman countryside going to the Macedonian countryside), but the truth is that the commotion caused by this incident it caused the two armies to quickly prepare for combat, fearful of an attack from their enemy.

In fact, it is even explained that, due to the hasty March, the leaders of both armies entered combat without armor and even without helmets, unprotected.

The problem with the Macedonian phalanx is that, in order for it to work, it must be a compact structure and move slowly, well put together.

Otherwise, spaces are opened that can be used by the enemy to penetrate the lines of the phalanx and disarticulate it. causing a large number of deaths and injuries, since inside, and once overcome and penetrated, the defenders have it difficult to move.

Perseus made a huge mistake: instead of advancing the auxiliary units up the side of the mountain, he did it with the phalanx.

The irregularity of the terrain and the haste that both sides had to take to enter the combat caused precisely those spaces to be opened in the Macedonian phalanxes.

This made it easier for the legionaries to penetrate between the Falangist lines, stabbing the Macedonian warriors who they could do little to move their seven-meter long sarissas, before the versatile short swords of the Romans.

I know esteem that the Macedonian forces suffered some 20,000 casualties in just one hour of combat, against a scant hundred deaths in the Roman field.

Perseus ran to take refuge in the city of Pidna, to later march to the capital of his kingdom, Pella, being captured by the Romans.

The consul Lucio Emilio Paulo divided Macedonia into four different republics, all of them vassals of Rome, and took the monarch Perseus to Rome together with his two sons. With the death of Perseus, a few years later, the Antigonid dynasty is considered extinct.

Themes in Battle of Pydna